Americans pay more for drugs and medical devices than any other country. Big Pharma follows potential patients everywhere — on TV, in print and online. Companies spend billions advertising to doctors to get them prescribe their brand-name drugs and devices. They also spend billions paying criminal and civil settlements resulting from fraudulent marketing. Do these practices empower patients or expose them to newer, riskier and more expensive drugs and devices?

Download Now

“[T]his advertising promotes only the most expensive products, it drives prescription costs up and also encourages the 'medicalization' of American life — the sense that pills are needed for most everyday problems that people notice, and many that they don’t.”

Convincing people they are sick and need a drug is a multi-billion dollar industry. In 2015, Big Pharma dropped a record-breaking $5.4 billion on direct-to-consumer (DTC) ads, according to Kantar Media. And it paid off for Big Pharma. The same year, Americans spent a record $457 billion on prescription drugs. The U.S. and New Zealand are the only countries where DTC is legal. Americans also pay more for drugs and devices than any other country.

The bulk of these ads appear on TV at a rate of 80 ads per hour of programming, according to Nielsen. Behind the drug and device ads saturating TV, radio and digital media are hidden costs and devastating side effects that companies don’t advertise, and critics say the ads drive up drug prices and erode the patient-doctor relationship.

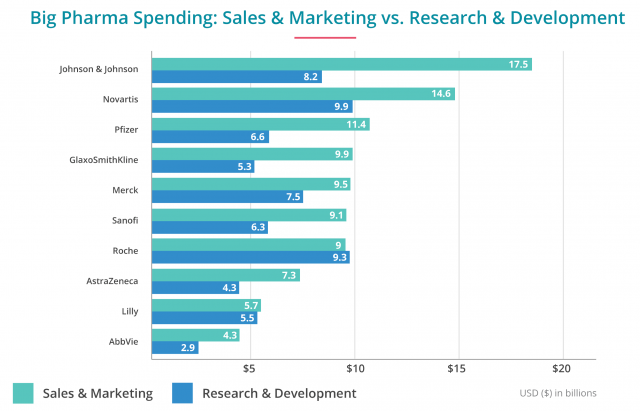

With the price of drugs skyrocketing, politicians and health-care providers question Pharma’s DTC spending, which exceeds money spent on research and development. Even presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton called for an end to tax breaks for drug ads and for tougher regulations.

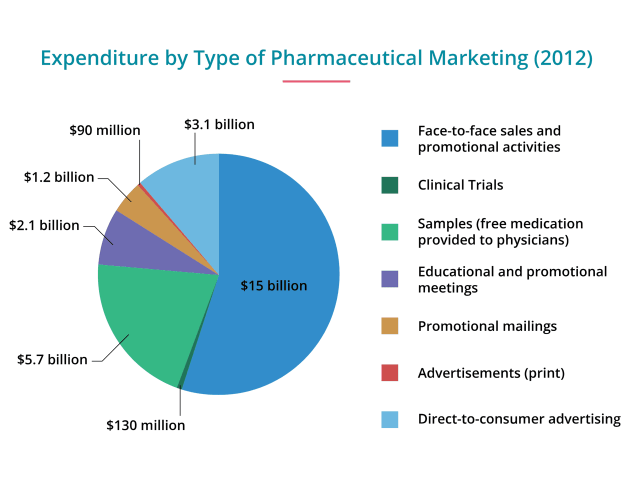

But the money spent on DTC is just one small cog in Big Pharma’s well-oiled marketing machine. Companies spend billions more on getting doctors to write prescriptions for their expensive brand-name drugs or devices for uses not approved by the Food and Drug Administration — a controversial practice called off-label marketing.

The darker side of pharma marketing involves creating clinical trials aimed at influencing doctors and educational courses to showcase expensive drugs for non-FDA-approved uses — even when there is no scientific proof of safety or efficacy.

Big Pharma has paid billions of dollars in criminal and civil settlements over the years because of marketing fraud that cost taxpayers billions and left others with debilitating medical conditions. For example, the Department of Justice accused Johnson & Johnson of spending billions to target children and the elderly for unapproved drug uses, exposing them to serious side effects, including death.

Supporters argue DTC ads educate the public and empower them to make better health-care choices and say the First Amendment protects them. Doctors and other critics say Big Pharma’s sole purpose is to sell expensive products that may have unknown side effects.

The American Medical Association and American Society of Health-System Pharmacists called for a ban on DTC, reigniting the conversation about pharmaceutical marketing. But the facts behind Big Pharma’s tactics show the issue is far more complicated.

The ABCs of DTC

When most people think of pharmaceutical or medical device marketing, they think of the ads they see while watching their favorite TV shows or football game or while browsing a magazine. If it seems as if there are more ads than ever, there are. Over the past four years, the amount of money spent on DTC ads grew 60 percent.

As of 2022, the top four TV networks — CBS, ABC, NBC and Fox — take the majority of the advertising budget, with CBS at the top of the list at $511 million. Ads for erectile dysfunction, arthritis pain and blood thinners dominate the airwaves. Although digital media ads are increasing, older audiences still favor TV. The average CBS viewer is 59, which is the target age for most of these drugs.

- Product claim ads

- These ads talk about a drug, the condition it treats and its risks and benefits.

- Reminder ads

- These ads "remind" people about the drug's name, but do not talk about its uses.

- Help-seeking ads

- These ads talk about a disease or condition without discussing specific drugs.

“And if you’re a pharma company, and you want to reach a lot of people quickly … there’s really no better place to go still than the traditional networks,” Timothy Calkins, a marketing professor at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, told STAT. “Pharma companies know who they’re going after, and they really focus on reaching those people.”

Though companies spend the bulk of their budget on TV — about $4 billion — magazines follow a close second, with about $1.5 billion spent in 2015, according to Nielsen. Newspapers, radio, billboards, movie theaters and other types of advertising only took up a few million dollars combined.

Arguments For and Against DTC

DTC has several supporters and critics. Both sides base their argument on a handful of pros and cons.

According to the FDA, DTC raises a few controversial issues, these include:

- Misleading or false information

- May threaten public health

- Not enough info on risks

- Encourages expensive treatments

Supporters claim DTC:

- Educates the public

- Increases communication between physician and patient

- Reminds patients to take medication

Regardless of the pros and cons, Big Pharma’s motivation comes down to money. Its biggest reason to keep dropping billions on advertising to consumers is that it works. The FDA approved a record 51 new drugs in 2015, and companies are scrambling for market share.

DTC Works

“Drugs with DTC ads had nine times more prescriptions than those that did not.”

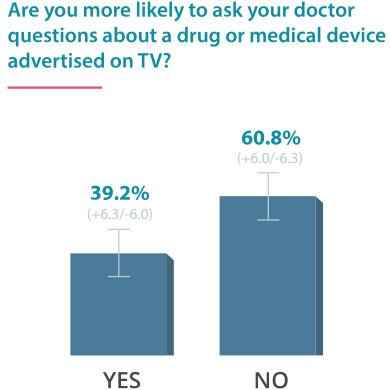

According to Kantar Media, two-thirds of adults take some kind of action after seeing a drug or device ad, and about 40 percent make an appointment with their doctor. Americans also have a high level of confidence in these ads when it comes to drug dangers, and about 76 percent feel drug companies adequately explain side effects and risks, according to a survey by Harvard and STAT.

“Americans tend to think newer is better. If it costs more, therefore it’s better. If it’s new and it costs more, then certainly it is better,” Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research, told Drugwatch. “They sometimes think that the FDA only approves new drugs if they are better. There is no requirement in the law, nor does the FDA require that a new product be better. I’ve heard FDA officials say, ‘We’ve approved this drug. It doesn’t mean we recommend it.’”

In fact, about 43 percent of Americans think only completely safe drugs are allowed to be advertised, according to Pew Charitable Trusts.

They have so much confidence in these drugs’ safety and effectiveness that they ask their doctors to prescribe them. Sales of drugs with DTC ads increased 43 percent versus just 13 percent for all other drugs, according to an article from the Journal of the National Cancer Institute. For every dollar spent on advertising to consumers, sales of prescription drugs rose $4.40.

Behind the TV Ad

“Consumer Reports has long held that drug ads should be banned...For one, they encourage patients and doctors to turn to medication when nondrug options might work. And when drugs are needed, ads often promote more expensive options, not the best or safest.”

How well do drug ads stand up to scrutiny? According to Consumer Reports, many drug ads are misleading and could encourage patients to seek expensive treatments. It sides with the AMA and ASHP in favor of a ban on DTC. The nonprofit organization cited a 2014 review published in the Journal of Internal Medicine. The data revealed 57 percent of claims in 168 drug ads were potentially misleading and 10 percent were entirely false.

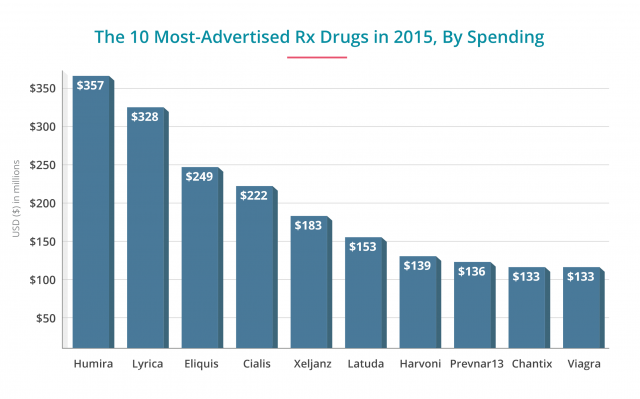

Drug companies tend to pour the most money into advertising newer, more expensive drugs. Consumer Reports published a review of some of the most popular drugs, including costs, risks and benefits. According to the report, newer isn’t always better. All the benefits portrayed in these colorful TV commercials mask hidden side effects and costs the drug companies don’t advertise.

- Viagra (sildenafil) and Cialis (tadalafil)

- At $70 for a 10-pill supply of Cialis (Eli Lilly) and $332 for 10 pills of Viagra (Pfizer), these drugs are some of Pharma's staple moneymakers. And the amount of money spent advertising them reflects this. Pfizer and Eli Lilly spend half a billion annually on ads. Millions of men take these medications to treat erectile dysfunction. But they can increase the risk of heart attack, stroke and vision and hearing loss.

- Humira (adalimumab)

- AbbVie's blockbuster drug for Crohn's disease was the heaviest hitter in revenue spent on ads at $357 million in 2015 — an all-time high for the drug. A month's supply of this drug costs about $5,000. Though research shows the drug works, it also increases the risk of tuberculosis and pneumonia.

- Xarelto (rivaroxaban)

- These two newer blood thinners reduce the risk of blood clots caused by atrial fibrillation and other issues. Blood clots can lead to strokes. Xarelto had an ad budget of about $106 million in 2015, and Eliquis spent more than double that, at $246 million. Each drug also costs about $300 a month versus warfarin, the decades-old blood thinner. Consumer Reports recommended warfarin over these newer drugs for cost and safety profiles. Xarelto in particular may cause internal bleeding, and without an antidote to stop the bleeds, they can be fatal. Patients have filed thousands of lawsuits against Johnson & Johnson's Janssen unit in courts across the country. Eliquis edges out Xarelto in safety and effectiveness versus warfarin.

- Lyrica (pregabalin)

- Second only to Humira in dollars spent on ads at $338 million, Pfizer's drug to treat fibromyalgia and epilepsy costs about $260 a month. Yet studies show only a modest benefit in patients who take the drug. Patients also face a wide range of side effects, including suicidal thoughts, liver and kidney problems, blurred vision and swelling. The company agreed to pay $43 million in fines for misleading marketing in 2012. The company faced a number of lawsuits for suicide and other side effects.

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib)

- Pfizer spends $183 million to advertise this newer rheumatoid arthritis drug. The drug is effective at easing pain but is not as well-studied. Serious side effects can include perforations in the stomach and intestines. The monthly cost is about $2,380. Consumer Reports recommends older generic drugs or better brand-name drugs such as Humira or Enbrel.

- Abilify (aripiprazole)

- In 2014, Abilify was the top-selling drug in the U.S. and made about $7 billion that year. The drug treats depression and costs about $900 a month. According to the ad, it helps people in whom other antidepressants don't work. But Consumer Reports found that it provides little if any benefit. Scientists aren't even sure how the drug works. The drug is linked to a host of side effects such as compulsive behaviors, heart attack, stroke and involuntary movements. Consumer Reports refused to recommend this drug.

History of DTC Marketing

TV ads are so prevalent that it is hard to believe DTC advertising is a relatively new concept. Before the 1980s, drug and device companies focused on marketing to doctors and pharmacists. But in the 1980s, the FDA relaxed regulations on ads targeting consumers — and Big Pharma seized the opportunity to reach a massive audience. Pfizer and Eli Lilly led the way, and billions of dollars later, the marketing shows no sign of stopping.

-

1958

About 90 percent of Big Pharma marketing is aimed at doctors. Its salesmen — called "detail men" — made 20 million calls to doctor's offices, paid for 3,790,809,000 pages of ads in medical journals and sent 741,213,000 pieces of direct mail.

-

1962

Kefauver-Harris Amendments strengthened the premarket review process and transferred regulatory authority of prescription drugs to the FDA. Drug companies must provide information about contraindications, side effects and effectiveness in all advertisements.

-

1969

FDA required drug ads be a "true statement of information in brief summary relating to the side effects, contraindications, and effectiveness.” Pharma still targets physicians as its main audience.

-

1980

FDA relaxes DTC marketing rules.

-

1982

Pfizer launches "Partners in Health Care” to increase awareness of hypertension, diabetes and depression. Eli Lilly advertises Oraflex to TV networks and radio stations. It emphasizes that the drug might stop arthritis, a claim not approved by the FDA. The drug is pulled five months later because of adverse events.

-

1985-90

Pharma advertises at least 24 drugs directly to the public. Companies begin branding over-the-counter medications in DTC ads. "Lifestyle" drugs for depression, erectile dysfunction and hair loss became popular.

-

1992

The AMA says the "era of health care reform" demands "individuals [take] responsibility for their health care, which means they will need more information." DTC prescription medication advertising climbs from $12 million in 1989 to $340 million by 1995.

-

1999

FDA releases "Guidance for Industry: Consumer-Directed Broadcast Advertisements." The guidance requires that broadcast ads give brief information about the major risks instead of a long summary of risks and warnings.

-

2005

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) issues "Guiding Principles: Direct to Consumer Advertisements About Prescription Medicines." This guidance adds the "ask your doctor" language to DTC ads.

-

2007

Advertising by pharma companies to consumers reaches $4.8 billion a year.

-

2011

Congressional Budget Office releases "Potential Effects of a Ban on Direct-To-Consumer Advertising of New Prescription Drugs." Study finds drugs with DTC have nine times more prescriptions that those that do not.

-

2014

FDA considers having fewer risks mentioned in DTC broadcast ads.

-

2015

American Medical Association votes in favor of DTC ban.

-

2016

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists votes in favor of DTC ban.

Doctors and Pharmacists Support DTC Ban

Doctors and pharmacists favor banning DTC ads altogether. They say the ads drive patients to demand newer, more expensive drugs when more cost-effective choices are available. The practice drives up cost of care and erodes the patient-doctor relationship.

For example, an article in the Journal of Clinical Oncology showed that 94 percent of nurse practitioners had patients ask for a drug they saw advertised, and 74 percent of them had patients request inappropriate drugs. Doctors wrote prescriptions for more than half of these requests.

In November 2015, the American Medical Association’s House of Delegates — its policymaking body of 540 grass-roots physicians — voted to back an advertising ban for prescription drugs and devices.

“The nation’s physicians are concerned that a growing proliferation of commercially-driven promotions is fueling demand for new and more expensive treatments regardless of the clinical effectiveness of less costly alternatives.”

“Today’s vote in support of an advertising ban reflects concerns among physicians about the negative impact of commercially driven promotions, and the role that marketing costs play in fueling escalating drug prices,” said AMA board Chair Dr. Patrice A. Harris. “Direct-to-consumer advertising also inflates demand for new and more expensive drugs, even when these drugs may not be appropriate.”

A few months after the AMA voted to ban DTC, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists followed suit in June 2016. The group’s news release cited a Government Accountability Office report noting that “pharmaceutical companies have increased spending on DTC advertising more rapidly than they have increased spending on research and development” and that “DTC advertising appears to increase drug spending and utilization.”

“For decades, pharmacists practicing in hospitals and clinics have been the leaders in recommending and initiating evidence-based medication therapies in partnership with physicians and other prescribers — and in helping patients achieve optimal and cost-effective medication therapy outcomes,” ASHP CEO Paul W. Abramowitz said in a statement.

The vote to ban all DTC ads is a radical change from the group’s former position that ads be allowed as long as they met certain criteria. According to the GAO report, “FDA’s oversight of DTC advertising has limitations.”

DTC and Its Effect on Drug Costs

“Pharmaceutical companies have been spending money like drunken sailors.”

The relationship between money spent on marketing and higher drugs costs is difficult to ignore. Though a number of things influence drug prices, Big Pharma’s argument for rising medication costs has long been the idea that it takes a lot of money to bring a drug to market. Companies are quick to say high research and development costs force them to charge higher prices to recoup what they spent.

But the truth is they spend much more money on sales and marketing than on R&D. For example, in 2013, one of the biggest drug companies in the world, Johnson & Johnson, spent more than double its R&D costs on marketing.

Doctors, pharmacists and critics of DTC are quick to point out that the cost of marketing a drug causes the price of the drug to rise. However, few studies exist.

According to a study cited by The New York Times, about 6 percent of rising drug prices are related to marketing. One study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine by Law, M.R. and colleagues followed one of the most advertised and popular blood thinners, Plavix (clopidogrel). The FDA approved the drug in 1999, and its DTC campaign began in 2001.

Researchers studied data from 27 Medicaid programs from 1999 to 2005. From 2001 to 2005, money spent on DTC exceeded $350 million. DTC did not increase number of units sold, but the price of the drug increased by $0.40 after the ads began. This might not seem substantial, but it equated to an additional $40.58 of pharmacy costs per 1,000 patients each quarter.

Spending on DTC ads led to an extra $207 million in pharmacy expenditures for that specific period.

Some lawmakers are sure drug costs increase because of ads. In 2016, House Rep. Rosa DeLauro called for a three-year moratorium on drug ads for new drugs, and Sen. Al Franken introduced a bill that eliminates drug company tax breaks for ad campaigns.

“[Drugmakers are] trying to encourage Americans to buy the most expensive drugs — even when cheaper, equally effective drugs are on the market. … This is just a common sense measure to help cut down health care costs,” said Franken in a statement.

“Proposals to eliminate the tax deductibility of DTC advertising ignore the value of informing patients about their health care and treatment options,” a spokeswoman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America wrote STAT. “An unintended consequence of eliminating [the tax deduction] may be fewer patients seeking medical care for chronic conditions that could be managed earlier and more cost-effectively.”

Consumer Marketing Encourages Overmedication

Doctors also agree that DTC ads encourage patients to seek out drugs. In fact, 81 percent of doctors surveyed in 2013 agreed that the ads promoted overuse of medications.

For example, take the “Low-T” campaigns for testosterone drugs such as AndroGel, Axiron and Aveed. FDA approved these drugs to treat men diagnosed with clinical hypogonadism, a condition that causes low testosterone. Drug companies billed these drugs as the new fountain of youth, promising increased vitality and sexual prowess.

Millions of men demanded their doctors prescribe these drugs, and many of them did so without a clinical diagnosis. Low-T clinics popped up in strip malls across the country.

“There are a total of 7.5 million prescriptions a year, and in the petition we filed, we only focused on the AndroGel and the patches and the oral drugs — that’s about 5 million,” Dr. Sidney Wolfe of the advocacy group Public Citizen told Drugwatch. “There’s another 2.5 million prescriptions for the injectable form, so it’s a widely used drug. As I said, a majority of the people should not be getting it. They’re not getting any benefit.”

“Obviously, the companies are paying a lot of money for these ads for a reason. They know it affects how many people take these drugs and how many prescriptions are written. And to pretend that they don’t know what the impact is seems disingenuous at best.”

The problem of over-prescription became so widespread that the FDA released a warning in 2015 stating there was no evidence the drugs were safe or effective for low libido and fatigue — key symptoms of low T featured in drug ads. But that did little to discourage the testosterone therapy craze.

According to Wolfe, millions of men were exposed to a drug with benefits that did not outweigh the risk of potentially fatal heart attacks and strokes. Several studies linked these drugs to increased odds of such cardiac problems. Lawsuits filed by thousands of men who claim the drugs caused a number of health issues soon followed.

Other studies point to the connection between the number of prescriptions and DTC ads. For example, doctors in the U.S. prescribe medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder about 25 times more in the U.S. than in the United Kingdom, a country that does not allow DTC. The validity of ADHD diagnosis has long been controversial, as has treating it with powerful antipsychotics. Each year, drug companies make $13 billion in prescriptions to treat it, according to a video report from Wired.com.

Dominick L. Frosch, a professor at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, published one of the first studies to analyze overmedication and DTC ads. Frosch and colleagues examined 38 unique TV drug ads for a number of ailments, including high blood pressure, cholesterol and depression.

The study found the ads appealed viewers’ emotions to encourage drug use and had little to do with concrete information.

“We’re seeing a dramatization of health problems that many people used to manage without prescription drugs,” Frosch said in a news release. “The ads send the message that you need drugs to manage these problems and that without medication your life will be less enjoyable, more painful and maybe even out of control.”

The Positives of DTC

“The days of Dr. Kildare sort of being the all-knowing doctor are over. Active, empowered patients who are expected to be very active in their own healthcare lead the culture in our times...it is important for consumers to be a part of the decision-making, to learn about options that are available to them and discuss them with their doctor. [DTC] is all about patient empowerment.”

Though DTC has many critics, it also has passionate supporters. Their biggest argument for advertising directly to consumers is the benefit of education and promoting awareness of treatment options.

“Patients who ask about a drug [they see on DTC ads] are more likely to get a better standard of care than those who don’t ask. So the conversation-starting part of direct-to-consumer advertising is a benefit to the patients,” John Kamp, executive director of the Coalition for Healthcare Communication, told Drugwatch.

Based in New York, CHC has been advocating the “free flow of truthful health-care information” for about 25 years. Kamp took the mantle of executive director 12 years ago and was one of the organization’s founders. CHC is an offshoot of the 4A’s — the American Association of Advertising Agencies. His background includes a stint practicing law and teaching constitutional law. Founded in response to an anti-DTC campaign by then-FDA Commissioner David Kessler, the organization ardently defends the right of drug companies to advertise under the First Amendment.

Kamp was critical of the AMA’s stance on banning DTC.

“I find it interesting that the only ones who can prescribe the drug think that the advertising for consumers changes the nature of the situation,” he said. “They are the decision makers. I don’t believe in the dumb or impotent doctor theory that doctors don’t have good conversations with their patients.”

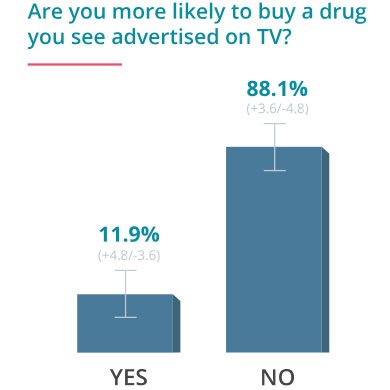

He also says the idea that patients take more drugs just because they see an ad is unfounded.

Some data support Kamp’s assertion. In a 2016 Harvard poll, only 7 percent said they would actually consider taking a drug advertised. A 2007 survey published in Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research showed 44 percent of patients said DTC ads helped educate them about drugs, medical conditions and treatment options. The ads also appear to affect patient compliance with treatment. In an FDA survey, 18 percent of patients said the ads reminded them to take their medications.

Nearly 80 percent of people said DTC ads increased their awareness of new drugs, and 73 percent of doctors said their patients asked thoughtful questions regarding DTC drug ads.

Critics: Ads Don't Educate

“If the real goal is to educate, they wouldn’t look like this. The goal is to persuade. These ads educate people as much as the ads for the GAP or ads for makeup educate. It is educating you to tell you that this product exists and that it's great.”

Though patients may feel drug ads educate them about treatments and diseases, there is insufficient evidence that people actually retain helpful information. In fact, findings in studies actually show people’s memories are skewed toward remembering benefits in DTC ads and not the risks.

DTC supporters say drug ads adequately explain risks.

“All you have to do is watch an ad to see that the risks take up one-third to one-half of the ad,” Kamp said. “In no other category [of product] do you get the fair balance that the FDA requires in consumer advertising of drugs.”

That might be true, critics argue, but rattling off a list of side effects actually works in the drug companies’ favor. The litany of side effects is so overwhelming, and most patients don’t pay attention. Most ads don’t discuss findings in clinical trials, either — especially if it’s a serious risk.

“Technically, the ads are supposed to reflect the studies that were submitted to the FDA, but a lot of times they don’t,” Zuckerman said. “For example with Farxiga, people in the clinical trials were five times more likely to be diagnosed with bladder cancer. Who in their right mind would want a diabetes medication that increases your risk of bladder cancer when there are so many diabetes medications?”

In addition, most ads exceed the eighth-grade reading level requirement, according to 2010 review by UCLA’s Frosch and colleagues, making it more difficult for the majority to understand. Experts say this exploits patients and could lead to making decisions based on incomplete facts about a drug or disease. In fact, patients with lower incomes and education levels who are less likely to seek medical care in general were more likely to see a doctor after seeing DTC prescription drug ads.

Studies also showed that risk data on product websites were also more difficult to find, whereas the benefits were on the first page.

“You know every consumer of advertising pays whatever attention they do,” Kamp said. “The information is there if you want to see it… They are not perfect, not everybody pays attention to every part of them, but they are there to warn consumers that every drug has side effects that you should pay attention to. They are not perfect, and no consumer of advertising watches them with 100 percent attention.”

Doctors and other health-care physicians said patients shouldn’t get information from drug ads at all.

“ASHP believes that medication education provided by pharmacists and other providers as part of a provider-patient relationship is a much more effective way to make patients aware of available therapies, rather than relying on direct-to-consumer advertising,” ASHP’s Abramowitz said.

Does DTC Advertising Work?

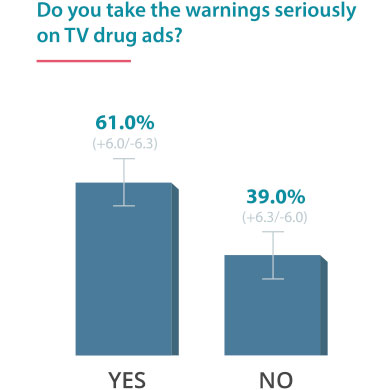

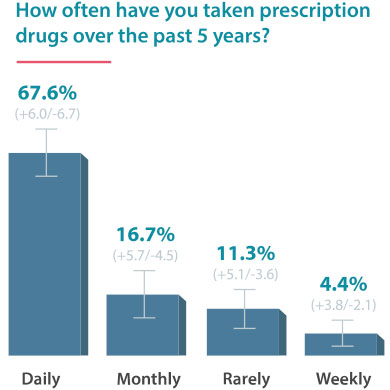

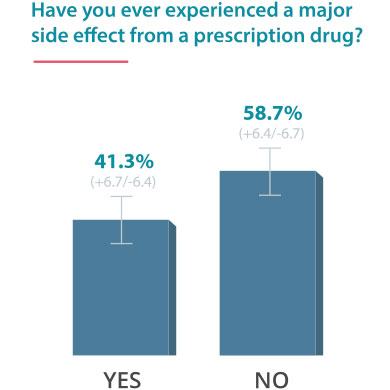

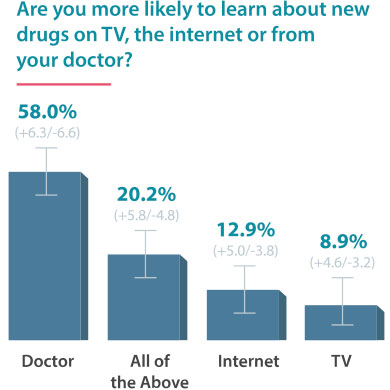

On June 24, 2016, Drugwatch conducted an online survey via Google Consumer Surveys about DTC advertising. The following results account for 237 responses amongst people age 55 and up.

Some Docs Find DTC Helpful

“What causes doctors to dislike DTC? Well, maybe some of them would prefer to go back to the era... when they were seen as deity and having all the information that anybody needed... I can only speculate. But, I think the recently press has made more of it than there actually is.”

Kamp said the AMA’s decision is unlikely to encompass the views of all doctors. Some actually find DTC helpful.

“A lot of doctors pushed back the proposal to eliminate DTC and didn’t think it was such a good idea,” Kamp.

Some surveys show doctors actually have a positive view of DTC. One from 2013 revealed 64 percent believed ads encouraged patients to contact a health-care professional.

Evidence shows that DTC might also promote general health awareness, not just pill popping. In 2010, a Prevention Magazine survey reported 29 million patients spoke with their doctors after seeing a DTC ad, and the majority discussed lifestyle changes and nonprescription or generic drugs over brand-name medications.

In addition, for every $28 a drug company spends on these ads, doctors get one more patient visit. Ads can also encourage patients with stigmatized conditions such as mental illness —depression in particular — to seek treatment, according to The New York Times.

Though patients with depression are more likely to seek treatment, they do not always get a prescription for the advertised drug. Doctors ultimately control the prescriptions, and sometimes they choose nonpharmaceutical treatments.

Celebrities Spreading Drug Awareness

A large part of pharmaceutical marketing involves celebrities. From famous athletes to actors, Big Pharma has used them throughout the years to help sell a drug or promote awareness of a disease or condition.

One of the more recent ads featuring not one but four celebrities is a TV commercial for the blood thinner Xarelto (rivaroxaban). The ad features celebrity golfer Arnold Palmer, NASCAR driver Brian Vickers, comedian Kevin Nealon and two-time NBA champion Chris Bosh extolling the benefits of Xarelto. These include being able to eat “healthy salads” and not having to check with a doctor for blood tests such as the ones required of patients on warfarin — a decades-old blood thinner.

Noticeably absent from the commercial is the drug’s risk of serious uncontrolled bleedingand lack of an antidote to stop the bleeds, such as vitamin K for warfarin. Bosh missed a number of games and Vickers wasn’t allowed to race while on the drug because of uncontrolled-bleeding concerns.

“This personal connection makes it a very real crusade for these spokespersons. They are armed with information, and they are using their recognizability to educate their fans.”

This ad is a perfect example of a branded ad — meaning all celebrities featured mention the drug by name and are actually taking or have taken the drug. Unbranded ads featuring celebrities raise awareness about a certain condition, such as Cedric the Entertainer talking about Type 2 diabetes on behalf of a drug company without mentioning the name of a drug.

“Unbranded campaigns allow for greater flexibility in my role,” Doner told Drugwatch. “That is to help match the pharmaceutical company with the right spokesperson who has or knows someone with a particular medical condition who then speaks out either personally or on behalf of a family member or friend.”

Doner connects pharma companies with celebrities and worked with actors such as Kelsey Grammer and Rob Lowe and drug companies such as GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson & Johnson. Before founding the Amy Doner Group, she planned events and handled media relations for Big Pharma heavy hitters such as Novartis, Merck, Pfizer, Glaxo and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

“Patient and physician dialogue is key to ensuring patients are better involved in and more informed about what might lie ahead when faced with — or trying to rule out — a medical condition,” Doner said. “Direct-to-consuming marketing can help to create this dialogue, and often a key driver to generating awareness for patients to even consider such a dialogue.”

These tactics work.

One of the first celebrities to raise awareness about erectile dysfunction was Bob Dole. In 1999, Pfizer, the maker of blockbuster erectile dysfunction drug Viagra, paid Dole to talk about ED. In 2000, “Today” show host Katie Couric — whose husband died of colon cancer in 1998 — underwent a colonoscopy on live TV to raise awareness about screening for the disease. Colonoscopy rates jumped 20 percent immediately following the broadcast.

But, although celebrity ads provide some positives, when they promote a dangerous drug, the ramifications can be disastrous.

For example, Bruce Jenner and Dorothy Hamill teamed with Merck to promote the painkiller Vioxx. Then-head of the American Arthritis Foundation Dr. John Klippel appeared on “Larry King Live” with the two Olympians and praised the drug for its lack of side effects.

“That’s one of the important things, Larry: Vioxx was developed to reduce side effects,” Klippel told King. “So if you will … it’s a safer drug to use.”

Four years later, Merck recalled the drug after some people taking it suffered heart attacks. In one of the largest health-care settlements in history, the drugmaker paid $4 billion to settle 35,000 lawsuits filed by people who said they suffered heart attacks.

Is Big Pharma Writing Your Prescription?

“In 2012, the pharmaceutical industry spent more than $27 billion on drug promotion — more than $24 billion on marketing to physicians and over $3 billion on advertising to consumers (mainly through television commercials). This approach is designed to promote drug companies' products by influencing doctors' prescribing practices.”

Though most consumers have experience with DTC, few know that Big Pharma spends billions more on marketing to doctors. Even the AMA and ASHP don’t address this in their votes to ban DTC. Drug companies employ a wide variety of techniques to reach prescribers. Free meals, speaking fees, and sponsoring educational courses and clinical trials are some of them.

It turns out that it doesn’t take much to sway a doctor. In fact, drug companies can get physicians to prescribe a drug for the price of a sandwich.

A 2016 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine revealed that doctors who accept free meals from Big Pharma tend to prescribe a company’s promoted drugs. Researchers looked at Medicare prescribing information for statins, blood pressure medications and antidepressants. After looking at data from 279,669 physicians, they found that just one free meal equated to higher rates of prescribing heavily promoted drugs Crestor (rosuvastatin), Benicar (olmesartan) and Pristiq (desvenlafaxine).

The study found all it took was a meal less than $20 to increase prescriptions for a branded drug. If the cost of a meal exceeded $20 or a doctor received additional meals, prescriptions rates were likely to go up even more. Authors said that, although the study does not prove a cause-and-effect relationship, there is an association between the two.

But this isn’t the only study to show this relationship between payments and prescribing drugs or devices. A 2016 ProPublica analysis of Big Pharma payments made to doctors also showed an increase in brand-name prescriptions.

“Indeed, doctors who received industry payments were two to three times as likely to prescribe brand-name drugs at exceptionally high rates as others in their specialty,” ProPublica found.

A spokesperson for Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, the industry trade group, told ProPublica that many factors affect doctors’ prescribing decisions.

“Working together, biopharmaceutical companies and physicians can improve patient care, make better use of today’s medicines and foster the development of tomorrow’s cures,” she wrote. “Physicians provide real-world insights and valuable feedback and advice to inform companies about their medicines to improve patient care.”

| Company | Number of Payments | Payment Totals |

|---|---|---|

| Genentech, Inc. | 6,486 | $388 million |

| DePuy Synthes Products LLC | 2,565 | $94.7 million |

| Topera Inc. | 298 | $93.1 million |

| Stryker Corporation | 120,404 | $90.8 million |

| AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP | 968,562 | $90.7 million |

| Medtronic Sofamor Danek USA, Inc. | 45,180 | $85 million |

| Pfizer Inc. | 738,451 | $82.5 million |

| Zimmer Holding Inc. | 47,417 | $70.5 million |

| Allergan Inc. | 343,906 | $69.9 million |

| Arthrex, Inc. | 15,152 | $58.9 million |

Marketing Campaigns Disguised as Clinical Trials

“Some company-sponsored trials of approved drugs appear to serve little or no scientific purpose. Because they are, in fact, thinly veiled attempts to entice doctors to prescribe a new drug being marketed by the company, they are often referred to as 'seeding trials.”

Seeding trials are thinly veiled pharma attempts at marketing drugs to doctors and probably some of the most insidious forms of marketing.

“In an age of for-profit clinical research, this is the new face of scandal,” wrote Carl Elliott in The New York Times. “Pharmaceutical companies promote their drugs with pseudo-studies that have little if any scientific merit, and patients naively sign up, unaware of the ways in which they are being used.”

These supposed clinical trials have a few distinguishing characteristics. They employ physicians that are frequent prescribers of competing drugs of the drug being studied, are poorly designed and pay high fees to the physicians participating in the trial who prescribe the drug.

The true purpose of seeding trials remains hidden until court documents surface in litigation against pharma companies. Companies do not disclose the purpose of these trials to review boards, physicians or patients, and little information is available in the public domain on the practice.

“This practice — a seeding trial — is marketing in the guise of science. The apparent purpose is to test a hypothesis,” wrote Drs. Harold C. Sox and Drummond Rennie in an editorial in the Annals of Internal Medicine. “The true purpose is to get physicians in the habit of prescribing a new drug.”

One of the most famous examples of a seeding trial surfaced during legal proceedings against Merck for its pain reliever, Vioxx. The trial, named ADVANTAGE (Assessment of Differences between Vioxx and Naproxen To Ascertain Gastrointestinal Tolerability and Effectiveness), was supposed to assess the gastrointestinal safety of the drug. Results of the trial even appeared in peer-reviewed medical journals, according to a review published in the Annals of Internal Medicine by Dr. Kevin P. Hill and colleagues.

“This practice — a seeding trial — is marketing in the guise of science. [...] The true purpose is to get physicians in the habit of prescribing a new drug.”

But doctors or researchers didn’t actually design the trial.

According to internal documents, Merck’s marketing team designed the trial to reach “a key physician group to accelerate uptake of Vioxx as the second entrant in a highly competitive new class and gather data important to this customer group.” Merck even nominated the marketing team for its Best Physician Program Award. Merck later pulled Vioxx from the market after a large number of patients taking the drug suffered heart attacks.

Parke-Davis, now a part of Pfizer, conducted another example of a seeding trial on its seizure drug Neurontin. Inexperienced investigators and a flawed study design led to disastrous consequences. Not only did it not yield much useful information, but 11 study participants died and 73 experienced serious adverse events.

Pharma's Addiction to Off-Label Marketing

“Desperate to maintain their high profit margins, pharmaceutical companies have increasingly engaged in illegal activities, such as dangerous, illegal promotion of drugs for uses not approved by the FDA — a practice commonly referred to as 'off-label promotion.'”

One of the most controversial practices in pharma marketing is so-called off-label promotion: the marketing of a drug to doctors for a use not approved for the FDA. Though it is legal for health care providers to prescribe a drug for an off-label use, it is illegal for a drug company to encourage it because the FDA has not received data showing the drug is safe or effective for that use.

Unfortunately, off-label promotion happens more often than the American public knows. In some parts of medicine, such as pediatrics and psychiatry, there is more off-label than on-label use. Supporters say drug companies should be allowed to discuss it.

“The drug sponsor, the company that manufactures the drug, is usually in the best position to talk about off-label because they know more about the safe and effective use of their drug than any other institution,” Kamp said. “If Einstein were among us, the last thing we would want to do is say everybody can talk about the theory of relativity, but we won’t let Einstein talk about it because he’s the one that came up with the idea.”

In some cases, patients may get access to lifesaving treatments off-label. For example, this is often the case with experimental cancer treatments. Patients with rare, terminal diseases may also benefit. But the intentions of drug companies might not be as noble.

Because drugs are often FDA-approved for very limited uses, pharma companies are quick to exploit off-label uses to pad profits — often at the expense of patient safety. Officially, they damn the practice as illegal. Unofficially, they incentivize sales reps and even coach them on tactics to sell off-label uses to doctors, hospitals and other health care facilities, such as nursing homes. For some reps, bringing up ethics could mean getting fired.

One of those former sales reps was Melayna Lokosky. She worked for venture-funded startup Acclarent, now part of Johnson & Johnson’s Ethicon division, which bought Acclarent in 2010. Before that, she worked for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Schwarz Pharma.

“I’m living proof [of this practice],” Lokosky told Drugwatch. “When I started challenging that behavior at then-Johnson & Johnson’s Ethicon’s Acclarent, I was wrongfully terminated.”

Lokosky filed a whistleblower complaint in Los Angeles Superior Court in 2015 accusing Acclarent of off-label promotion of its Relieva Stratus MicroFlow Spacer for an unproven drug-delivery use. According to the complaint, J&J is liable for millions of dollars in damages stemming from insurance companies paying for medically unnecessary, misbranded Acclarent devices marketed to physicians for unproven off-label use.

William Facteau, who was CEO, and Patrick Fabian, who was vice president of sales — two former top Acclarent executives — face fraud charges in Massachusetts. A federal grand jury indictment said they marketed Acclarent’s Relieva Stratus MicroFlow Spacer off-label for delivering steroids. The FDA only approved the device for opening sinuses.

“Reps now, from recent rulings, can sell off-label if what they are saying is factual,” Lokosky said. “The problem with FDA giving the industry an inch, to sell off-label, is that they’ll take a mile, as we’re now seeing with the Johnson & Johnson Acclarent case.”

Off-Label Use Leads to More Side Effects

Using drugs off-label can also spur an increase in side effects. Of the top five drugs prescribed off-label, about 80 percent did not have strong scientific evidence for off-label use, according to a 2015 study in JAMA by Tewodros Eguale and colleagues.

The study looked at 151,305 prescriptions. About 7.6 percent of patients suffered adverse effects from the drug, but when the same drug was used off-label, the rate of side effects was 44 percent greater.

Marketing an Antispychotic to Children and the Elderly

One of the most publicized cases of off-label marketing in recent years centers around Johnson & Johnson’s off-label promotion of its antipsychotic drug Risperdal (risperidone). Originally, the FDA only approved the drug in 1993 to treat schizophrenia in adults. However, that didn’t stop J&J from marketing the drug to treat ADHD, anxiety, sleep difficulties, depression and hostility in groups at high risk for dangerous side effects — in this case, children and the elderly.

In early J&J trials, researchers found the side effects of the drug in children and the elderly were substantial, according to Steven Brill’s investigative piece “America’s Most Admired Lawbreaker.” Despite this, J&J’s Janssen unit exploited these two profitable groups.

“Risperdal is indicated for the management of manifestations of psychotic disorders,” Lisa Stockbridge, then of the FDA’s Division of Drug Marketing, Advertising and Communications, wrote to Janssen’s director of regulatory affairs. “However, Janssen is disseminating materials that imply, without adequate substantiation, that Risperdal is safe and effective in specifically treating hostility in the elderly.”

Of considerable concern to Stockbridge and the FDA was the large number of unexplained deaths from heart-related issues and strokes in elderly patients taking Risperdal. In fact, the agency denied J&J’s request for Risperdal approval for use in the elderly in 1999 because of safety issues. In particular, J&J “failed to fully explore and explain what appeared to be an excess number of deaths.”

One of the most controversial side effectsinvolved young boys and men growing breasts, a condition called gynecomastia. Court documents say J&J knew of the risk. But in the 1990s, Risperdal made about 20 percent of its revenue from sales to children — even if the FDA had no proof it was safe or effective in this group. J&J marketed it heavily for ADD and ADHD and paid reps heavy bonuses to promote it to doctors as safe.

“At the same time, the company focused on rounding up respected academics who could aid the cause by touting the results as they came in and make Risperdal the prime choice for pediatricians regardless of what the FDA label said,” wrote Brill in his article.

Lawsuits filed by parents and young men who suffered gynecomastia they say Risperdal caused poured into state and federal courts across the country.

In 2015, Austin Pledger won the first Risperdal jury trial. Pledger developed size 46DD breasts when he was a teenager after he started taking the drug at age 8. The jury awarded him $2.5 million after determining J&J failed to warn about the risk of gynecomastia.

Pharma Spends Billions on Marketing Fraud Fines

The Department of Justice collects billions of dollars in fines from drug companies routinely breaking the law. So far, the biggest settlement in American history belongs to GlaxoSmithKline. The company paid $3 billion to resolve criminal and civil charges related to illegal promotion of drugs and failure to report safety data. The drug at the heart of the controversy was its popular antidepressant Paxil. The pharmaceutical giant pleaded guilty for pushing the drug as a treatment for children younger than 18, though the FDA never approved it for this use.

“Off-label promotion can be prosecuted as a criminal offense because of the potential for serious adverse health consequences to patients from such promotional activities,” Dr. Michael A. Carome, director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, told Drugwatch.

According to a March 2016 Public Citizen study, “Twenty-Five Years of Pharmaceutical Industry Criminal and Civil Penalties: 1991 Through 2015,” federal and state governments and pharmaceutical manufacturers reached a total of 373 settlements totaling $35.7 billion.

“Many of the infractions, and the single largest category of financial penalties, stemmed from the practice of off-label promotion of pharmaceuticals,” Carome said.

Fines Won’t Stop Big Pharma

Regardless of hefty DOJ fines, experts say pharma won’t curb off-label promoting anytime soon — there is just too much money to be made. Lack of oversight from federal authorities and the medical community allows drugmakers to find loopholes in the laws, Forbes reported.

“Despite the gaudy sums, however, it’s unlikely that the industry will curb its reliance on off-label prescriptions. The practice is simply too lucrative to pass up.”

Off-label prescriptions bring in about $40 billion each year or about 20 percent of all revenue, according to a report from Cozen O’Connor’s Life Sciences Practice Group. With figures such as these, Big Pharma is willing to sacrifice a few hundred million for a one-time fine.

In the case of Risperdal, for instance, off-label prescriptions accounted for 75 percent of sales in 2002. According to court documents, it was J&J’s second-best-selling drug, and off-label marketing catapulted the drug from sales of $172 million in 1994 to $1.7 billion in 2005.

The DOJ didn’t reach a $2.2 billion settlement until 2013 — that’s almost two decades’ worth of profit from off-label use.

| Company | Amount | Drugs | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlaxoSmithKline | $3 billion | Paxil, Wellbutrin, Avandia | 2012 |

| Pfizer | $2.3 billion | Bextra, Geodon, Zyvox, Lyrica | 2009 |

| Johnson & Johnson | $2.2 billion | Risperdal, Invega, Natrecor | 2013 |

| Abbott Laboratories | $1.6 billion | Depakote | 2012 |

| Zyprexa | $1.4 billion | Zyprexa | 2009 |

| Merck | $950 million | Vioxx | 2011 |

| Serono | $704 million | Serostim | 2005 |

| Purdue Pharma | $634.5 million | OxyContin | 2007 |

| Allergan | $600 million | Botox | 2010 |

| AstraZeneca | $520 million | Seroquel | 2010 |

| Bristol-Myers Squibb | $515 million | Abilify | 2007 |

Courses Designed to Sway Doctors

Wining and dining doctors isn’t the only way to influence prescriptions. Another way pharma and device companies reach health care providers is through continuing education programs. The law requires doctors to take continuing education courses to keep their licenses in 45 states. And pharma doesn’t have to disclose the money it spends on these programs.

Big Pharma has always been a big contributor when it comes to funding these courses, many of which are free for doctors. In 2014, course providers reported $2.7 billion in income, and about $676 million came from device manufacturers and drug companies, a Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and MedPage Today investigation found.

Tighter regulations requiring doctors to disclose funding and universities refusing drug company money led to pharma’s hiring third-party companies. These companies created materials, hired instructors and put on the courses.

“Consider it the dark money of medicine.”

“These companies want to get more money from industry, and they’re certainly not going to put on a course that doesn’t appeal to industry,” Paul Lichter, who heads the University of Michigan’s clinical and educational conflict of interest committee, told the Journal Sentinel “They know where their bread is buttered.”

The Journal Sentinel and MedPage Today reviewed 75 Big Pharma-funded courses for testosterone replacement therapy found half the faculty received drug payments, and 65 course instructors had ties to a company that makes or markets these products. And these courses focus on off-label uses.

Course materials often use studies funded by the drug industry or studies with dubious information. For example, one study only involved 13 men. Several studies show testosterone can contribute to prostate cancer, yet Abbott — the maker of AndroGel — promoted its use in men with active, low-grade prostate cancer. FDA-approved labels for the drug also say men with known or suspected prostate cancer should not use the drug.

The FDA's Role

“The FDA has written policies that sound good, but the reality is very different from the written policies.”

Contrary to what the public believes, the FDA has not deemed as safe all drugs that are advertised. In fact, the FDA sees the ads at the same time the public sees them. In the meantime, an unsuspecting public risks exposure to harmful drugs. In fact, the agency that many consumers rely on to provide oversight in all things drug- and device-related seems to be doing a poor job.

Only 33 percent of Americans think the FDA does a “good” job of regulating new drugs, according to a poll by Harvard and STAT. More than half think it does a fair or poor job.

So what does the FDA actually do when it comes to reining in pharma marketing? It turns out, very little, and any of the FDA’s guidelines for drug companies are voluntary.

“In most cases, federal law does not allow the FDA to require that drug companies submit ads for approval before the ads are used,” the FDA says on its website. “Many drug companies voluntarily seek advice from us before they release TV ads. However, if we believe that an ad violates the law, we send a letter to the drug company asking that the ads be stopped right away.”

The FDA’s drug company letters are getting fewer, too.

From 1997 to 2001, the agency sent an average of 111 letters per year, according to Public Citizen. But this number dropped to 29 a year from 2010 to 2014. The agency has also had the authority to issue an actual monetary penalty to manufacturers for illegal ads since 2007. Public Citizen asked the FDA in 2015 whether it ever assessed such a penalty, and it had not.

“The FDA is responsible for regulating drug marketing and promotion. Unfortunately, the agency does a poor job of monitoring DTC advertising,” said Public Citizen’s Carome. “Therefore, the FDA needs to be more vigilant in monitoring DTC advertising, dedicate more resources to the oversight of pharmaceutical company marketing, and take more aggressive enforcement actions against companies that engage in misleading advertising.”

Other FDA critics took an even tougher tone.

In 2002, critics slammed AstraZeneca’s print and broadcast ads for tamoxifen, saying they overstated the benefits and understated the risks. The FDA approved the drug for healthy women at high risk for developing breast cancer. The drugmaker’s ad boasted a 47 percent reduction in new breast cancer incidence after five years of therapy and minimized serious risks such as uterine cancer and blood clots.

It took the FDA six months to respond, a lag exposing millions of women to a potentially dangerous side effects and incomplete evidence of efficacy.

“The FDA regulations are drafted and enforced in such a way that encourages drug companies to cross the line — with a lack of resources to identify violations and enforcing these regulations,” said Barbara Brenner, executive director of Breast Cancer Action, in 2002. “They do not have the resources to monitor drug ads prior to publication, so the burden of monitoring these ads then falls on the public.”

Instead of Banning Ads, Demand Transparency

The call to ban DTC ads is years old. Unfortunately, the AMA, ASHP and countless consumer groups are unlikely to get such a drastic decision passed by Congress. The truth is drug advertising and its supporters are protected by the Constitution. Not only that, powerful lobbyists protect them. With DTC gone, a lot of organizations stand to lose billions. This includes advertisers and media that accept such ads.

“We have seen versions of this legislation before, and it’s not surprising that it rears its ugly head again in this campaign season,” said Kamp. “But the premise and the public policy are just plain wrong. … Laws that ban truthful messages are a violation of the First Amendment.”

Instead of an outright ban on DTC, Kamp suggested the FDA and other regulators focus more on what really matters: making sure companies tell the truth.

“I think it is time for FDA to take a leadership role and to take this more in the direction of false and misleading, because false and misleading advertising is never allowed,” he said.

Part of the truth should include a demand for more transparency. For instance, drug companies should be required to submit specific information about DTC and other advertising expenditures. The Physician Payments Sunshine Act requires drug companies to report their payments to doctors, for example. This change in legislation makes physicians think twice before accepting money from Big Pharma. It also lets consumers know of possible conflicts of interest.

“You know that the current US Supreme Court has ruled that corporations are people and that money may speak as people, so don't hold your breath.”

If the ads are here to stay, improve them. What consumers really want to know are the costs, harms and trials as well as benefits. For example, simple tables with this information should be featured in print and TV ads. One study in the American Journal of Public Health found even consumers of lower education levels understood information presented in a quantitative table.

Other advocates suggest a drug scorecard from the FDA. The card might feature comparative data of new drugs and older ones with information on cost and clinical trials, reported The New York Times.

When dealing with drugs and medical devices, patients shouldn’t have to wonder whether they will suffer a serious side effect, be disfigured or even die as a result of lack of information or misleading advertising driven by profiteering companies. Unfortunately, when it comes to many of these products, it is a case of “buyer beware.”

Though a ban is unlikely, signing petitions and reaching out to Congress are still good ways to speak out and raise awareness.

“Even if you think of it as a free speech issue, there is the problem of yelling ‘fire’ in a crowded movie theater,” said Zuckerman of the National Center for Health Research. “When can you say, ‘This has such a negative effects that it shouldn’t be allowed’? Many of us think we’re there.”

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch.com representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch.com's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.