Black Box Warnings

A black box warning is the FDA’s most stringent warning for drugs and medical devices on the market. Black box warnings, or boxed warnings, alert the public and health care providers to serious side effects, such as injury or death. The FDA requires drug companies to add a warning label to medications that have a black box warning.

- Medically reviewed by Mireille Hobeika, Pharm.D.

- Last update: March 11, 2025

FDA black box warnings take their name from the black border around the warning information. The information in the box must have a header in all caps and information printed in bold typeface. These warnings notify the public of serious, permanent or fatal side effects.

Boxed warnings first appeared on medications in the 1970s. While drug companies are responsible for creating the information on a drug label, only the FDA has the authority to issue a black box warning.

Once a drug receives a black box warning, its manufacturer must also create a medication guide that describes how patients can safely use the drug. These guides come with the medication at the pharmacy and are available online on the FDA website.

Black box warnings warn the public, but also alert doctors and other prescribers to serious side effects. Some evidence suggests, however, that these warnings may go unnoticed by doctors, putting patients at risk.

According to studies, drugs that go through the FDA’s fast track programs for quick approval are also more likely to require black box warnings a few years after they hit the market. The FDA is also using more black box warnings than ever before.

In 2022, the FDA issued 28 medical device Safety Communications, and five drug safety communications as of Nov. 30, 2022. None of these included adding a black box warning to the product.

FDA’s Black Box Warning Process

Before adding a boxed warning to a medication or medical device, the FDA must have evidence that the drug poses a significant risk. This evidence comes from observations and studies conducted after a drug has been on the market.

Unfortunately, this means that new drugs that have just hit the market typically will not have these warnings and people who take these drugs may be at increased risk for a serious unknown side effect.

After determining a drug needs a black box warning, the FDA contacts the drug company to add a warning to its labeling. The drug company then submits its language for FDA approval. Once the FDA approves the language, it is printed on the drug or device’s package and on the medication insert.

The FDA uses boxed warnings to highlight risks in the following situations:

- If evidence shows a drug causes a serious adverse reaction — potentially fatal, life-threatening or permanently disabling — where the risks might outweigh the benefits

- A serious side effect can be avoided or reduced in severity or frequency by appropriate use of the drug, such as avoiding use in specific situations, observing patients, careful patient selection or avoiding using the drug with certain medications

- The FDA approved the drug only for restricted use to ensure public safety

- The drug is less effective or dangerous to certain populations such as the elderly, children or pregnant women

The FDA doesn’t often remove warnings, but when it does it requires clinical evidence proving that the drug’s risks are less severe than previous studies show.

Abilify

Use

Depression, bipolar disorder

Warning

Suicidal thoughts in youth, death risk in elderly with dementia-related psychosis

Accutane

Use

Severe acne

Warning

Birth defects

Actos

Use

Type 2 diabetes

Warning

Heart failure risk

Avandia

Use

Type 2 diabetes

Warning

Congestive heart failure

Benicar

Use

High blood pressure

Warning

Fetal toxicity

Cipro, Levaquin and Avelox

Use

Antibiotics

Warning

Tendon rupture, peripheral neuropathy, central nervous system effects

Cymbalta

Use

Depression, anxiety

Warning

Suicide risk

Depakote

Use

Epilepsy

Warning

Birth defects, liver toxicity, pancreatitis

Essure

Use

Birth control

Warning

Perforation of the uterus and/or fallopian tubes, pain, allergic reactions, device migration

Invokamet, Janumet, Kazano

Use

Type 2 diabetes

Warning

Lactic acidosis related to the metformin component

Power Morcellators

Use

Fibroids

Warning

Risk of spreading uterine cancer

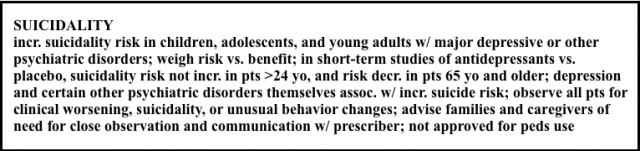

SSRIs and SNRIs

Use

Depression, anxiety

Warning

Suicide risk in children

Testosterone

Use

Hypogonadism

Warning

Exposure to women, children

Risperdal

Use

Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder

Warning

Death risk in elderly with dementia-related psychosis

Issues with Boxed Warnings

The boxed warning has been the FDA’s go-to for flagging dangerous drugs. There are studies that show it is effective in reducing the use of medications in people at risk of severe side effects.

For instance, antipsychotics like Risperdal have a black box warning for increased death in older patients. A 2010 study published in Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine) by Dr. E. Ray Dorsey and colleagues showed that antipsychotic use fell after the FDA added a black box warning, especially among seniors with dementia.

But critics still find flaws in the system. These include lack of compliance by doctors, discouraging people from taking medication and lack of transparency on the black box process.

Lack of Physician Compliance

Some experts say black box warnings are not effective because some physicians don’t pay attention to them — and if they do, it is inconsistent.

A 2005 study by Dr. Anita Wagner and colleagues published in Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety revealed that the range of compliance with black box warnings among doctors varied from 0.3 to 49.6 percent.

“Our study shows wide use of black box warning drugs and that prescribing compliance with the warnings varies, and thus suggests a potential for harm. The wide use of black box warnings makes it very hard for prescribers to know what is important and what is really important.”

In the case of power morcellators or Essure Permanent Birth Control, the FDA requires patients to sign patient consent forms that show their doctors explained the risks to them.

May Discourage People from Taking Medication

While black box warnings can decrease use of the medication for at-risk-populations, they might also discourage people who need medication from taking it, studies show.

Christine Y. Lu and colleagues at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute published a 2014 study in the British Medical Journal. They found black box warnings decreased antidepressant use but increased the suicide attempt rate among young people.

“The FDA, the media and physicians need to find better ways to work together to ensure that patients get the medication that they need, while still being protected from potential risks,” Lu said in a Harvard press release.

Lack of Transparency

Researchers say that the FDA’s process for adding or removing warnings is not clear enough, especially when the FDA decides to remove a previous warning.

In 2016, Harvard researchers stated that making the process more uniform and transparent could increase the public’s confidence in the warnings. James Yeh and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School wrote their opinions in Drug Safety.

Researchers point to two instances where drug makers approached the FDA to remove black boxes on their medications with weak evidence.

In the first case, Pfizer petitioned the FDA to remove a black box for “severe psychiatric events” and suicide from its smoking-cessation aid Chantix. After a committee meeting and reviewing the five short-term studies Pfizer presented, the FDA opted to keep the warning.

But in the second case, GlaxoSmithKline was successful in getting the black box for heart problems removed from its Type 2 diabetes drug Avandia. It provided data from one randomized trial.

Researchers said FDA must require more evidence to remove a warning.

“To avoid frequent flip-flopping, we believe it is ethically justified for the FDA to require a greater burden of proof, or a greater level of certainty provided by the evidence at hand, to justify removal of a boxed warning than it did to impose one,” they wrote.

Fast-Tracked Drugs Are More Likely to Have Boxed Warnings

Drugs that the FDA gives fast-track status to are more likely to receive a boxed warning after they hit the market, according to a 2017 study by Andreas Schick and colleagues.

Ideally, fast-track reviews get drugs to patients who need them sooner, but there may be a safety cost. The FDA’s quick review could mean the agency does not have enough time to analyze data for side effects.

Standard reviews for drug approval can take about 10 months. A drug that receives fast-track approval can be on the market in six months.

In the study, researchers looked at approximately 200 drugs submitted to the FDA since 1997 and launched before 2010. Manufacturers eventually pulled 11 of these drugs from the market for safety reasons and 30 received boxed warnings.

Authors said fast-tracked drugs were 3.5 times more likely to receive a boxed warning after they already made it into the hands of patients.

Increased Use of Black Box Warnings

In the last several years, the FDA has approved record numbers of new drugs. While drug approvals are up, so are their safety risks — many of these lead to black box warnings.

In a 2017 JAMA study by Nicholas S. Downing and colleagues, researchers found that nearly a third of all drugs cleared by the FDA pose a safety risk.

It took the agency a little more than four years on average to take action against the drugs reviewed in the study.

More Action Needed from FDA

While black box warnings remain an important tool in warning the public, some doctors feel the FDA needs to do more to encourage compliance from prescribers.

“Our study adds to evidence of other studies showing that black box warnings do not work well as risk communication tools.”

“Our study adds to evidence of other studies showing that black box warnings do not work well as risk communication tools,” Dr. Anita Wagner said in a Medscape interview. “In fact, perhaps in response to limited adherence to black box warnings, the FDA and manufacturers increasingly implement strengthened risk management programs for certain drugs.”

Wagner suggested the FDA take a more aggressive approach such as the warning and reporting process implemented for users of Accutane.

The drug carries a black box for severe birth defects, but wholesalers, pharmacies, doctors and patients have responsibilities for ensuring women who take the drug are not pregnant or plan to be pregnant. Under the mandatory iPLEDGE program, pharmacists must have a current negative pregnancy result on file from women in order to dispense the drug.

Calling this number connects you with a Drugwatch.com representative. We will direct you to one of our trusted legal partners for a free case review.

Drugwatch.com's trusted legal partners support the organization's mission to keep people safe from dangerous drugs and medical devices. For more information, visit our partners page.